The Untold Story of Industrial Soapmaking History: From Cottages to Factories

History of Soap Making: From Medieval Guilds to Industrial Revolution (Part 2)

In our previous post, we explored the fascinating origins of soapmaking in ancient civilizations. We discovered how the Babylonians, Egyptians, and Romans developed early cleansing substances that laid the groundwork for what would eventually become soap as we know it today. Now, let’s continue our journey through the rich history of soap making, exploring how this essential craft evolved from medieval guilds to industrial powerhouses – and eventually circled back to the artisanal methods we cherish at Seattle Sundries.

Medieval Soapmaking: Craft, Culture, and Constraints

As the Roman Empire fell, much knowledge was lost – including many soapmaking techniques. However, the craft gradually reemerged throughout Europe during the medieval period, evolving from crude household necessity into a regulated commercial product with distinct regional identities.

Soap as a Luxury Few Could Afford

Would you believe that something as basic as soap was once considered a luxury? Throughout medieval times, soap remained largely inaccessible to common people – not because it couldn’t be made, but because of deliberate government policies.

Soap was heavily taxed by various kingdoms, positioning it as a luxury rather than a basic necessity [7]. Most ordinary folks had limited access to manufactured soap, resorting to making crude, functional versions at home [8]. These homemade concoctions were typically gloopy and less refined than commercial varieties – a far cry from the beautiful bars we craft today at Seattle Sundries!

The expense of quality soap was considerable – a cake of Castile soap in 14th century England cost about 4d, roughly equivalent to two-thirds of a skilled laborer’s daily wages [9]. Given this prohibitive cost, washing with plain water remained the norm for most people. Meanwhile, Queen Elizabeth I’s documented preference for Castile soap highlights its prestigious status among European royalty [8].

“When we look at these historical pricing structures, it makes us appreciate how accessible quality soap has become today. At Seattle Sundries, we believe everyone deserves access to naturally crafted soap – not just royalty!” - Anne Sylte Bloom, Founder

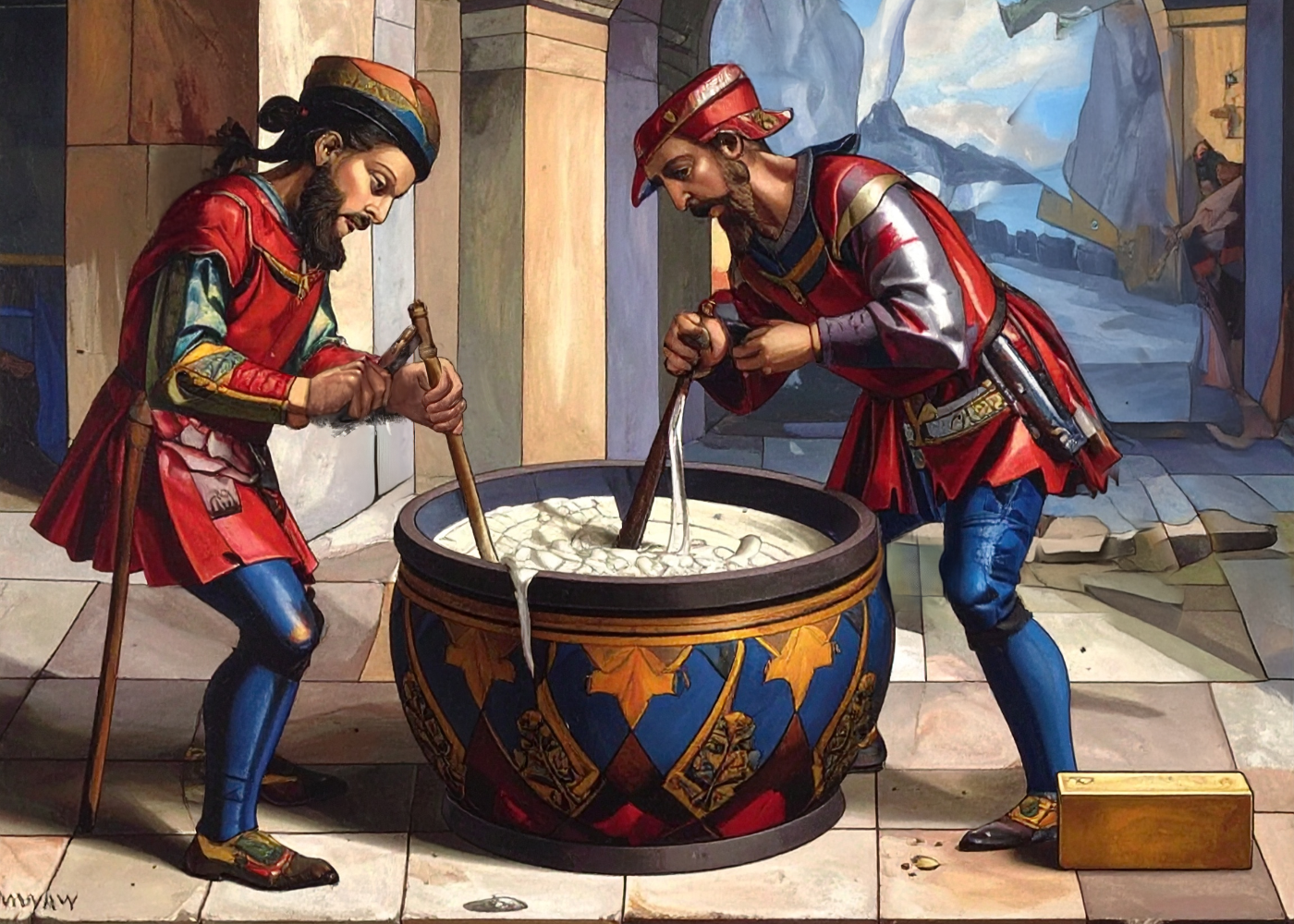

The Rise of Soapmakers’ Guilds

By the 17th century, soapmakers’ guilds had become established institutions throughout Europe [7]. These organizations regulated the craft’s secrets, carefully guarding production techniques and controlling quality standards. The training and promotion of craftsmen within the trade were highly regulated, with knowledge passed meticulously from master to apprentice.

Guild formation had begun much earlier in some regions—Naples had organized soapmakers as early as the late sixth century [5]. In fact, Charlemagne’s Capitulare De Villis, dating to approximately 800 CE, specifically mentions soap as one of the products royal estate stewards were required to inventory [5].

Throughout the 13th century, soapmaking in Britain became concentrated in large towns like Bristol, Coventry, and London, with each developing distinctive local varieties [2]. The profession gained such prominence that Richard of Devizes noted around 1200 CE that virtually everyone in Bristol was or had been a soapmaker [10].

This guild system of knowledge-sharing and quality control inspires our approach at Seattle Sundries. While we don’t keep our methods secret (in fact, we love sharing them in our workshops!), we do maintain strict quality standards and a commitment to craftsmanship that would make those medieval guilds proud.

Castile and Marseille: Centers of Soapmaking Excellence

Two regions emerged as particularly renowned centers of soapmaking excellence: Castile in Spain and Marseille in France. Both regions benefited from abundant olive oil supplies and high-quality alkali sources [2].

Castile soap earned its distinguished reputation from its pure white appearance and mild nature. Spanish soapmakers used olive oil rather than the laurel oil found in their Middle Eastern inspirations, largely due to supply constraints [8]. The region benefited from a special alkali called barrilla, derived from saltwort plants native to Spain, which produced exceptional soda ash [11]. This ingredient was so valuable that selling its seeds outside Spain was punishable by death [11].

Similarly, Marseille’s soapmaking industry, established after the Crusades, expanded beyond artisanal production by the 16th century [12]. By 1660, Marseille hosted seven soap factories producing nearly 20,000 tons annually [12]. Under Colbert in 1688, Louis XIV issued an edict regulating “Marseille soap,” requiring it contain only pure olive oils and prohibiting animal fats [13]. This regulation cemented Marseille’s reputation for excellence.

At Seattle Sundries, we draw inspiration from these historical centers of excellence. Our commitment to using high-quality, sustainable ingredients that promote gentle cleansing and moisture retention [citation from research workbook] echoes the standards set by these medieval masters.

Different Soaps for Different Purposes

Did you know that medieval soap served distinctly different purposes, with specific formulations for each use? In fact, soap was primarily developed for industrial applications rather than personal hygiene—specifically for preparing wool for dyeing in the textile industry [2].

Castile soap came in different varieties: white for skin cleansing and black for fabric washing [9]. In Northern Europe, where tallow replaced olive oil in soap formulations, the resulting products were softer, more caustic, and primarily used for laundry [9]. These harsh soaps left washerwomen with blistered hands and legs – definitely not something we’d want to use on our skin today!

The distinctions between Mediterranean and Northern European soaps were substantial:

-

Mediterranean countries produced hard, mild soaps using olive oil and imported soda ash from Egypt and Syria [9]

-

Northern European countries relied on animal fats, creating softer, more caustic soaps [9]

Despite advancements in soapmaking, most medieval Europeans primarily used soap for laundry rather than personal hygiene [8]. Oftentimes, personal cleanliness involved plain water, as soap remained too valuable to “waste” on bathing for all but the wealthiest individuals [1].

At Seattle Sundries, we’ve studied these historical distinctions and incorporated the best aspects of traditional soap making methods into our products. We focus on creating gentle, skin-friendly formulations using natural ingredients – combining the mildness of Mediterranean traditions with locally-sourced ingredients that would make our Northern European ancestors proud.

The Rise of Industrial Soapmaking

The 18th and 19th centuries marked a transformative era for soapmaking as cottage industries evolved into commercial enterprises. This period witnessed unprecedented growth in soap production techniques, distribution networks, and consumer marketing that forever changed how soap was manufactured and sold.

How the Industrial Revolution Transformed Soapmaking

Throughout the Industrial Revolution, soapmaking underwent dramatic changes as mechanization replaced manual methods. Prior to this period, soap remained largely a household product or small guild-controlled craft. The introduction of steam power, improved transportation, and growing urban populations created ideal conditions for soap’s evolution into mass-produced commodities.

By the mid-1800s, industrial advancements propelled soapmaking onto a fast track of development [14]. Cities flourished with commercial establishments while print media expanded product awareness. The mechanization of equipment to handle large quantities, coupled with efficient transportation methods, provided the foundation for widespread soap distribution [14].

The demand for soap increased substantially as urban populations grew and industrial settings required higher cleanliness standards [15]. This period also saw significant changes in social norms around cleanliness, as the combination of better soaps and advances in plumbing, including running water and drainable bathtubs, made bathing the social norm [2].

Steam Power and Chemical Innovations

Steam-powered machinery revolutionized production efficiency, creating economies of scale under more controlled conditions [2]. Chemical innovations likewise transformed soap manufacturing. Nicholas LeBlanc’s invention of the soap press and the discovery of chemical processes to make soda ash and caustic soda fundamentally changed production capabilities [4].

The 1853 repeal of the British soap tax by Gladstone—a centuries-old financial burden—allowed the industry to flourish [2]. This tax elimination coincided with Nobel’s invention of dynamite, which utilized glycerine (formerly a waste product of soapmaking), adding another revenue stream for manufacturers [2].

While we appreciate these innovations that made soap more accessible, at Seattle Sundries we’ve chosen to maintain traditional methods that preserve the natural glycerin in our soaps. Unlike industrial processes that often extract this valuable moisturizing component, we ensure it remains in our bars for enhanced skin hydration [citation from research workbook].

The Birth of Soap Branding and Advertising

Major soap companies emerged during this period, establishing brands that would dominate for generations. William Procter and James Gamble formed their partnership in 1837, reaching sales of one million dollars by 1859 [16]. Their innovative “floating soap,” discovered accidentally when a worker left a soap-mixing machine running too long, became Ivory Soap in 1878 [14][16].

Other prominent manufacturers included William Colgate, who opened his New York City factory in 1806 [14], and Andrew Pears, who developed his transparent soap in early 1800s England [14]. William Hesketh Lever and his brother James founded Lever Brothers in 1885, producing “Sunlight Soap” at a rate of 450 tons weekly by 1888 [14].

Advertising became increasingly sophisticated as companies competed for market share. Between 1890 and 1920, the soap market exploded partly in response to sanitation reform movements [17]. Companies utilized innovative marketing strategies including:

-

Product differentiation between household and toilet soaps [17]

-

Creating memorable slogans like Ivory’s “99 and 44/100% pure” [16]

-

Developing print advertisements aimed at different target groups [16]

At Seattle Sundries, we take a different approach to marketing than these early industrial giants. Rather than mass advertising, we focus on authentic connections with our community, sharing the genuine story behind our products and the traditional soap making techniques that inspire us. We believe transparency about our ingredients and processes is the best form of advertising! ✨

From Taxed Luxury to Mass Commodity

For nearly one and a half centuries, soap remained inaccessible to common people across Britain, not for lack of manufacturing capability but because of deliberate government policy.

The Burden of Soap Taxes

The British monarchy began heavily taxing soap in 1712, effectively transforming it into a luxury commodity [3]. Throughout this period, soap manufacturing faced unprecedented government scrutiny. Revenue officials closely supervised production, ensuring equipment remained locked away when not in use [5].

Manufacturers were legally required to produce a minimum of one imperial ton per boiling—a quantity impossible for small-scale producers [5]. This regulation effectively eliminated cottage industry production and concentrated manufacturing among larger companies.

Facing these constraints, many British soapmakers relocated to Ireland or the American colonies where soap taxes didn’t exist [8]. The government’s strict control effectively stunted innovation—manufacturing techniques remained largely unchanged from Queen Anne’s reign through the early 19th century [6].

Freedom to Innovate: The Repeal of Soap Tax

By the 1830s, the British soap industry showed troubling signs of decline. Production fell from 160,374,000 pounds in 1835 to 152,114,157 pounds by early 1838—a decrease of nearly 7% [6]. The number of towns with soap manufacturers plummeted from 148 to just 83 [6].

Prime Minister William Gladstone finally repealed the soap tax in 1853, ending 141 years of restriction [8]. This decision created an immediate financial challenge, as soap duties had generated approximately £800,000 annually for the treasury [6]. Historians note that Gladstone introduced death duties to compensate for this loss [3].

Global Expansion of Soap Production

After the tax repeal, industrial soapmaking flourished. The combination of tax elimination, industrial machinery, and new chemical processes created ideal conditions for expansion [8]. By the mid-1800s, soap had become one of America’s fastest-growing industries [18].

Historically, major European production centers had already established themselves in Antwerp, Castile, Marseille, Naples, and Venice by the 15th century [5]. London dominated English production, while Marseille became France’s manufacturing hub, producing 20,000 tons annually by 1660 [5]. With barriers removed, soap finally transitioned from luxury to everyday necessity, fundamentally changing cleanliness standards across society.

At Seattle Sundries, we’re grateful for the removal of these historical barriers that allows us to freely practice our craft today. We believe that quality soap should be accessible to everyone, not just the wealthy elite – though we still maintain the artisanal quality that once made soap such a valued commodity.

Modern Shifts: Detergents and Artisanal Revival

The next evolution in soap history came with chemical innovations that permanently altered the industry landscape. World War I necessitated a different approach to cleaning when fats were needed for other purposes.

The Rise of Synthetic Detergents

German chemists pioneered the first synthetic detergents during World War I, creating short-chain alkylnaphthalene-sulfonates under the brand name Nekal. These products served primarily as wetting agents rather than cleansers. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, long-chain alcohols were sulfonated and sold as sodium salts, marking the true beginning of synthetic detergents [19].

By the 1940s, synthetic detergents had addressed soap’s most significant drawback—the tendency to form scum in hard water. Unlike traditional soaps, these new formulations remained effective regardless of water quality [19].

The Evolution of Liquid Soap

William Sheppard patented liquid soap in 1865, yet widespread adoption came much later [5]. B.J. Johnson’s palm and olive oil-based liquid soap became so successful by 1898 that his company renamed itself Palmolive [5].

Modern liquid soaps typically use potassium hydroxide instead of sodium hydroxide, creating a softer consistency [20]. Notably, liquid soaps command higher profit margins than bar soaps, with millennials generally preferring liquid formats for their perceived convenience and elegance [20].

At Seattle Sundries, we honor both traditions – creating both solid and liquid soaps using traditional methods and natural ingredients. Our liquid soaps maintain the same commitment to quality and sustainability as our bars, without the synthetic detergents that dominate most commercial products.

The Return to Tradition: Handmade Soap Revival

Following decades of synthetic dominance, handmade soap experienced a remarkable revival beginning in the 1960s and 1970s. This resurgence stemmed from growing awareness about chemical ingredients in commercial products [21]. Currently, the artisanal soap industry is projected to grow by over 20% within five years [22].

Eco-conscious consumers increasingly seek natural ingredients, sustainable packaging, and ethical production methods [23]. This movement celebrates transparency—allowing users to know exactly what touches their skin—while revitalizing traditional techniques once overwhelmed by industrial manufacturing [24].

Seattle Sundries proudly stands at the forefront of this artisanal revival. Founded by Anne Sylte Bloom with a vision to create essential, everyday products through traditional craftsmanship, our journey began in 2005 at local craft fairs in Seattle [citation from research workbook]. We’ve grown steadily since then, expanding into our first commercial space in 2015 and relocating to larger facilities in 2022 [citation from research workbook].

Our approach to soapmaking bridges historical traditions with modern sustainability practices. We’ve deeply researched and incorporated historical soapmaking methods, drawing inspiration from:

-

Babylonian Influence: Integration of traditional fat and wood ash combinations and adaptation of ancient chemical processes [citation from research workbook]

-

Egyptian Heritage: Use of natural vegetable oils and alkaline salts with a focus on therapeutic properties [citation from research workbook]

Yet we implement these traditional elements with modern sensibilities:

|

Traditional Element |

Our Modern Implementation |

|---|---|

|

Natural Ingredients |

Use of high-quality oils, butters, and botanicals [citation from research workbook] |

|

Handcrafted Process |

Each soap bar individually crafted with attention to detail [citation from research workbook] |

|

Glycerin Preservation |

Natural glycerin retained for enhanced skin hydration [citation from research workbook] |

Seattle Sundries: Carrying the Torch of Soapmaking Tradition

As we’ve journeyed through the fascinating evolution of soap from medieval luxury to industrial commodity and back to artisanal craft, it’s clear that Seattle Sundries stands as part of this rich historical continuum. We honor the guild traditions of quality and craftsmanship, the regional excellence of places like Castile and Marseille, and the return to natural ingredients that characterized pre-industrial soapmaking.

Our traditional product line includes items that would make our soapmaking ancestors proud:

-

Old School Almond Tallow Shave Soap: A traditional tallow-based formula with natural ingredients including castor oil and almond essential oil, packaged in eco-friendly aluminum [citation from research workbook]

-

Smooth Shave Soap: An all-vegetable ingredient formulation with a classic barbershop-inspired scent and rich, moisturizing lather [citation from research workbook]

Our customers appreciate these connections to tradition, frequently praising the rich lather creation with traditional badger brush, the moisturizing properties and gentle cleansing, and our natural ingredient selection [citation from research workbook].

As we look toward opening our new workshop and retail space in Fremont in 2025 [citation from research workbook], we remain committed to educational initiatives like workshops on traditional soapmaking and community engagement programs that share this rich history with others [citation from research workbook].

Looking Ahead: The Future of Soapmaking

The journey of soapmaking reflects humanity’s innovative spirit throughout the ages. From medieval guild secrets to industrial mass production and back to artisanal craftsmanship, soap has evolved while maintaining its essential purpose.

In our next and final post in this series, we’ll explore the modern soap industry, current innovations in sustainable soapmaking, and how traditional techniques continue to influence contemporary practices. We’ll also delve deeper into Seattle Sundries’ unique approach to blending historical wisdom with modern sustainability.

Until then, we invite you to visit our workshop, where you can see firsthand how we’re keeping these traditional soap making methods alive while creating products that meet contemporary needs for quality, sustainability, and effectiveness.

After all, at Seattle Sundries, we’re not just selling soap – we’re selling a piece of history, a story, a lifestyle that connects you to generations of soapmakers who came before us. 🧼✨

References

[1] - https://medievalbritain.com/type/medieval-life/activities/did-people-use-soap-in-the-middle-ages/

[2] - https://www.open.edu/openlearn/history-the-arts/history/history-science-technology-and-medicine/history-science/the-history-soapmaking

[3] - https://unrememberedhistory.com/2017/02/23/when-soap-was-taxed-bathing-was-optional-and-dying-was-too-expensive/

[4

Leave a comment